The Constraint Layer: Why Modern Systems No Longer Make Sense

How Feedback Inversion and Constraint Collapse sever meaning, language, and accountability.

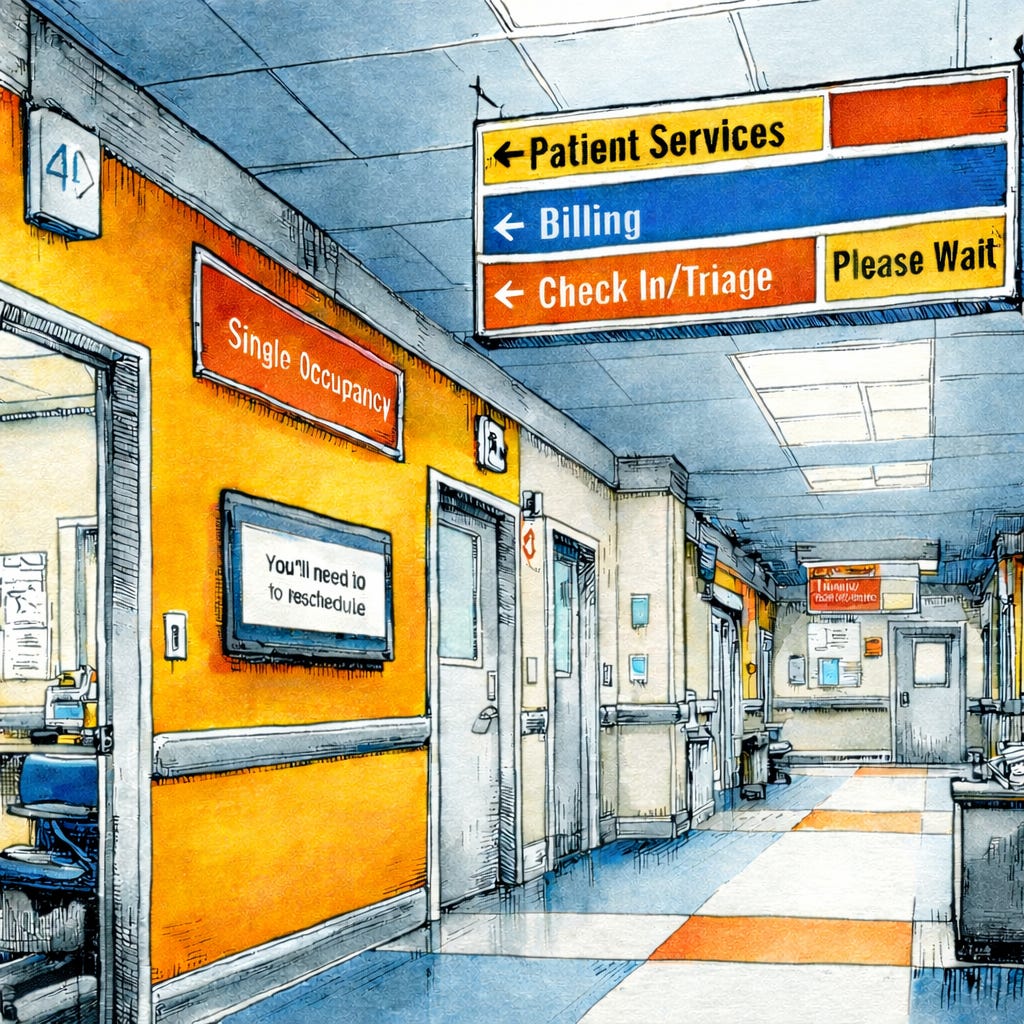

You log in to a patient portal to check a test result. The result is “available,” but not visible. You message your provider. An automated reply says they’ll respond in 48 hours. Three days later, a different provider replies with a template that doesn’t answer the question. You try again, but then are told that specialists can’t be messaged directly. A week later, still no response. But the bill has already arrived. The system is responsive. The information exists, but orientation never arrives.

Experiences like this have become so common that we barely register them anymore, but they point to a deeper structural shift that took hold in the mid-2010s, when large systems stopped reliably orienting people to reality while continuing to speak as if they still did. Not because of any single event, but because several slow-moving shifts crossed a threshold at roughly the same time.

Explanation as Continuation

Over this period, something subtle but consequential changed as institutions became faster, more frictionless, and increasingly articulate while the environments they mediated grew more complex. As digital mediation intensified, optimization began to outrun judgment. Interfaces improved, language grew more polished, and systems became better at maintaining continuity under pressure, but explanations quietly changed their function. They no longer helped people understand what was happening and instead helped systems continue operating without interruption.

This marks the beginning of what I call the Age of Drift, where the mechanisms that once bound shared language to lived constraint quietly weakened. A gap opened between institutional fluency and actual accountability, and it widened slowly enough to feel normal.

What broke follows a clear pattern across domains once you know what to look for. Feedback stopped biting as consequences became delayed, statistical, or externalized in ways that severed decisions from their costs. Being wrong no longer reliably produced learning or reversal, but instead produced explanation, narrative adjustment, and continued operation under modified assumptions. Incentives detached as upside concentrated and downside dispersed, allowing decisions to persist without anyone bearing the full cost of error. As explanations grew smoother, they grew less tethered to reality. At some point, fluency stopped being reassuring and started feeling like a warning sign.

Each of these breakdowns is survivable on its own, but together they produce a deceptively stable form of instability. Systems keep functioning while losing their ability to orient anyone to reality. They remain responsive, feedback continues to flow, but indicators that once corrected direction now reinforce motion. This is a feedback inversion, a second-order failure of the correction layer itself, where mechanisms meant to enable course correction instead stabilize drift and prioritize continuation. Over time, institutions lose orientation slowly, continuing to operate with confidence while the consequences are felt most by individuals.

The Legibility of Distrust

The signs of this failure were felt long before they were understood. One of the first signs was the emergence of a phrase that tried to name that feeling. Stepping back from its political overtones, the phrase “fake news” mattered because it was diagnostic, naming a felt recognition that something in the machinery of shared reality had slipped. Not that facts had disappeared or truth had become relative, but that the systems responsible for stabilizing meaning no longer felt grounded. Donald Trump did not invent distrust in reality but exposed how fragile it already was. The phrase worked because it pointed to a real failure mode, language that remained fluent while losing constraint, explanations that sounded right but no longer carried weight. The phrase survived long after its political moment because the underlying condition remained unresolved, a persistent sense that the systems mediating reality had become unmoored from the constraints that once gave their explanations force.

When Nothing Quite Binds

What the phrase captured at the level of language was already happening at the level of experience. Constraint loss operates wherever systems replace judgment with process, showing up less as outright failure than as a quiet thinning of responsibility. Parenting drifts into portals where everything is logged and tracked, yet no one is able to exercise discretion about what actually matters for a particular child in a particular moment. Healthcare billing speaks fluently in codes and procedures, but ownership disappears, appeals dissolve into structures no individual can navigate, and resolution never quite arrives. Customer service promises escalation in carefully scripted language that avoids any commitment binding an outcome to a person or a deadline. The surface shifts from domain to domain, but the experience is familiar.

What emerges is a strange sense of interchangeability, as if everything slides past without resistance. Netflix feels like Hulu not because their catalogs, but because both are optimized for continuation rather than choice. Work feels hollow because completion no longer binds to consequence in ways that create meaningful constraint. Nothing is obviously broken in the way institutional failure is usually recognized, but nothing pushes back either, and without resistance reality becomes hard to feel. This is what constraint loss looks like before anything visibly breaks.

Meaning Lives in the Negative Space

This pattern has been noticed long before it showed up in modern systems. Simone Weil wrote that reality is encountered through resistance, and warned that when resistance disappears, experience drifts toward illusion. In a different register, Terrence Deacon showed that meaning arises not from what is present but from what is absent, from constraints that shape possibility by excluding alternatives. Weil approached the problem as a philosopher of lived experience, while Deacon approaches it as a neuroscientist studying how meaning forms. But they are pointing to the same underlying structure from different directions. Meaning lives in negative space, in the boundaries and limitations that give shape to what can be said and done. Remove that negative space and communication smooths out, sounding better and traveling faster while losing its grip on anything real. This is why systems can feel confident while drifting. They still speak fluently and still coordinate action, but no longer know what they are constrained by.

Reality Is a Space of Constraints

If meaning depends on constraint, then the way we usually describe reality misses something fundamental. We tend to talk about reality as if it is made of objects, facts, or information, as if institutional failure is primarily a problem of incorrect data or misleading narratives. But reality is not primarily a collection of facts. Reality is a space of allowed moves shaped by constraints, defined by what can happen, what cannot, what costs something, what is irreversible, and what carries consequence. Meaning emerges when experience is compressed within a stable constraint space, and language works when it preserves the shape of that space as it moves between people and systems.

In other words, constraint describes the structure that gives choice form and prevents meaning from dissolving into noise. As that structure erodes, institutions lose their ability to bind language to consequence, and drift emerges as representations continue even when the territory they once reflected has lost its shape. This kind of failure does not announce itself as breakdown, but as a predictable misalignment that reshapes how systems operate.

The Constraint Axioms

From a systems perspective, it helps to distinguish between failures that operate independently and the behavior that emerges when they combine.

First-Order Failures

Each of these first-order failures can persist on its own while the system continues to appear stable.

Delayed or externalized consequence: Decisions lose direct contact with their costs. Errors no longer reliably force learning or reversal because consequences arrive late, statistically, or fall on someone else.

Compression without fidelity: Representations get optimized faster than they are grounded. Stories travel efficiently while carrying less of the constraint structure that once gave them weight.

Legibility outruns reality: At scale, systems reward narratives that allow coordination to continue, even when those narratives stop mapping to what is actually happening.

Continuation outpaces correction: Institutions run on accumulated trust and procedural momentum long after constraint integrity has begun to fail. People cannot.

Second-Order Failure

This failure does not appear on its own. It emerges when all four first-order failures accumulate and compound.

Constraint Collapse (Feedback Inversion): When these conditions combine, feedback continues to flow but stops correcting. Indicators that once produced learning now confirm continuation. Systems remain responsive while losing their ability to orient anyone to reality. The paradox is that systems grow more fluent and more confident even as they slowly decay.

People Carry the Cost First

What looks like stability at the system level registers very differently at the human level. Institutions run on stored order in the form of legacy trust, procedural momentum, accumulated capital, and social and psychological debt built over years. People do not have that buffer. Individuals feel the loss immediately because they require lived contact with reality in ways systems do not. Constraint loss shows up as exhaustion, cynicism, disengagement, and polarization, taking the form of burnout, overload, and the sense that nothing quite lands or leads anywhere.

This is why reality drift so often feels like a personal failure. The constraint layer that makes truth actionable erodes quietly, while the burden of orientation shifts onto individuals. As constraint thins in ways narratives can’t compensate for, language keeps moving even as it loses weight. As speed takes over, judgment and ownership fade, and decisions stop carrying real cost. Meaning returns only when judgment is allowed to reappear, tradeoffs are visible, and uncertainty isn’t immediately processed away so systems can keep going.

Until then, systems will continue to sound confident while drifting, and people will continue to feel that something is off long before they can explain why. That is the recursive trap of the Age of Drift. Eventually, things keep sounding right even after nothing quite holds anymore.

Further Resources:

[Anchors and Constraints: Practical Cognitive Hygiene in Modern Life] - Slideshare

[Cognitive Drift and Constraint Collapse in Optimized UX and AI Systems] - figshare

Brilliant breakdown of how systems keep operating while losing their grip on reality. The feedback inversion part really captures something I've felt at work lately, where every update and metric seems to confirm we're on track even tho we're clearly drifting further from what matters. Its like institutional confidence has inverted into a warning sign rather than reassurance. This constraint loss framework makes that feeling finally legible.